At times of need, during nights of tears, comfort is given by many people, including nurses and doctors. In ‘The Book About Getting Older’ Dr Lucy Pollock comfortingly states that the age at which we might not survive the year is 104.

She tells of a conversation with John whose mother lived alone and with dementia since the death years before of her husband years. ‘I’m sorry . . .she seems comfortable, and I think she is peaceful, but it doesn’t look as if our treatment is working. It’s really bad pneumonia, and I think she’s going to slip away.’

He looked stricken. She put her hand on his arm. His head was bowed, his shoulders hunched.

‘Sorry, doctor. It’s just – well, Dad died of heart failure and diabetes. And now Mum’s got dementia and pneumonia. I wouldn’t mind if it was natural causes, but all these diseases really get me down.’

What would ‘natural causes’ be, if not pneumonia or heart failure? It took her another twenty-five years of looking after very old people and their families to work out what John was talking about.

I commend the gentle Liz Earle Wellbeing conversation with Dr Lucy. One subject is how to discuss when driving should be restricted or ended.

A key point is that many people become happier as they pass into and through their seventies. There is no reason to mope or to be miserable all the time. I love meeting people fifteen years older than I am, listening to their current interests and hearing the earlier stages of their lives.

It helps when they have any necessary hearing aid. When my father, 17 years a widower with no help until the last week of his life, was 89, he accused me of mumbling while I suggested a hearing test. Both may have been right. He maintained health and happiness. We could have conversations about death and how he felt about life.

He was not bothered about whatever burial service or memorial came afterwards. After a period of quiet, he did say we could include our mother’s favourite psalm 150 (the sound of the trumpets, the loud cymbals) or one of the hymns based on it. After another pause, he suggested we read aloud a love poem he had written during WWII to her before they married.

He had warned her that his family in each generation, though not always in a direct line, had a golden wedding. One of his sisters had married an older man; the other was not likely to marry (though she did for 18 years, starting at age 64): marriage to him was likely to be more than a short-term engagement. He survived very serious wounding in Normandy; they gathered their descendants there about half a century later. Two of their surviving children have been married that long and two others are on their way.

Around the constituency, I meet family members and professional carers adding life to the closing years or weeks of our time on earth. Additionally, Virginia and I keep up with people who came to parliament ahead of us.

Recently, a former cabinet minister instructed us to mark an evening ten years on to hear his 100th birthday speech. This week, to note the overlap of Jewish Passover and the Christian Easter, we took chocolate and a special bottle of gin to friends who had guided and helped me to become and to continue serving as an MP.

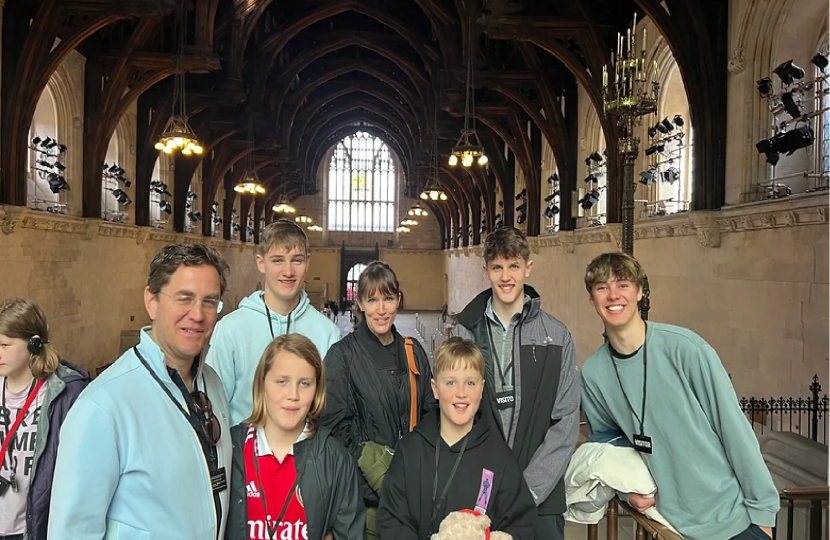

This week I took a cheerful family from Ireland around the Palace of Westminster. We noted points of special interest to them – and to me because of my mixed heritage. We did not duck the difficult events in history, including the assassinations of MPs colleagues by the IRA and the terrible way Oliver Cromwell’s troops acted in Ireland.

When politicians can establish peace, people can live, laugh and love.